As it is in many Aboriginal communities, the annual powwow is a day of celebration for the Eskasoni First Nation, one of the five Mi’kmaq communities in Nova Scotia’s Cape Breton Island.

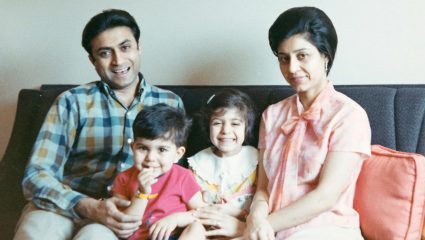

For Renee Sylliboy, who manages Eskasoni’s Foodland store, which is the only full-service grocery store in the community of nearly 4,000, the feelings the powwow evokes are deep.

“I’m really proud to be who I am,” says the 41-year-old mother of four, who is distantly related to long-ago Mi’kmaw Grand Chief John Denny Sylliboy.

Eskasoni’s powwow is a coming together of residents, past and present, and a showcase for Mi’kmaq history, culture and spirituality. “We’ve come a long way as a community,” she says. “In a way, this celebrates our survival.”

Renee — who was born in Eskasoni, and who lived elsewhere for her high school years and then returned — is an example of the strength of that community. She is fluent in the Mi’kmaq language and speaks it at home, as do her children who attended Mi’kmaq immersion school.

Her house is full of beautifully woven and decorated Mi’kmaq baskets. Every year Renee makes a pilgrimage to Chapel Island, in Cape Breton’s Bras d’Or Lake, the most sacred site for her people.

During the annual powwow she also does her part to honour her community, its elders and traditions. Her store, after all, supplies much of the food at the children’s picnic, one of the centrepieces for the powwow. She personally helps to persuade other vendors to donate food and prizes to make the day an unabashed success.

“We are a tight-knit community,” Renee says. “Everybody knows everybody and we all work together, our staff and our community, as a team.”

That was clearly evident in October 2016, when the tail end of hurricane Matthew brought high winds and heavy rain to Nova Scotia. Eskasoni bore the brunt of the storm as it passed over the province, causing flash floods in the community.

Winds knocked out the power and rivers overflowed, washing out roads on both ends of the reserve and flooding hundreds of houses.

Power outages meant a countless amount of food was spoiled throughout the community. That’s when Renee and Foodland jumped in to ensure no one went hungry.

Her store offered 30 per cent discounts on everything but tobacco and lottery tickets for residents of Eskasoni and the surrounding communities. Thanks to Sobeys, Foodland’s parent company, huge pallets of food arrived, both for the store and the barbecue that was held to lift people’s spirits.

At the store, there wasn’t an available shopping cart to be found. People were coming to get a load of groceries, going home, dropping it off, then coming back again for more. “It was great for the community,” says Renee.

So, the next Easter they decided to have another 30 per cent discount day. That event was successful enough that Renee is talking about making it an annual thing.

That sense of sharing and community and helping people in need is the norm in a place that has suffered the same kinds of grim hardships endured by indigenous people everywhere.

Sharing and community is the Sobey way too.

The emphasis on putting customers and people first, on supporting local and stressing community — and on helping those who need help — has been a guiding principle since the organization got its start 110 years ago, just a few hundred kilometres from Eskasoni.

Even today the original Sobey store in Stellarton extends credit to its neighbours.

During the Great Depression, Frank Sobey’s mother, Eliza, would never turn a hungry man away from her door. “If it weren’t for the likes of (Frank’s father) J.W. Sobey … we would have starved to death,” said a coal miner’s wife from that time.

The miners were J.W.’s best customers. He extended them credit, and on the Saturday payday they put money on their bills. During periods of illness, bereavement, disasters, or mine shutdowns, J.W. carried the mining families on his books until they were able to start paying back.

“A lovely man, a mild man, a fine, fine man,” someone once said of J.W. Sobey.

Later, Frank Sobey and his son William did their civic duty, serving their home community of Stellarton as mayors. In time, the family established The Sobey Foundation to improve the lives of individuals through investments in health, education and communities.

Today the tradition endures wherever the name Sobeys or the other members of its corporate family can be found. Much like in Eskasoni, where Renee does her part for the community in her own way.